Compare commits

218 Commits

| Author | SHA1 | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

98bb9f13da | ||

|

|

d375dc6ebe | ||

|

|

ee335bca82 | ||

|

|

601d8eb809 | ||

|

|

b99f350a18 | ||

|

|

c1b0e796c6 | ||

|

|

d9e65147c7 | ||

|

|

6001513c4f | ||

|

|

3fa033d8d5 | ||

|

|

59f7e66ac3 | ||

|

|

08e8dfccbe | ||

|

|

fc70a2f36f | ||

|

|

f5c5dbb739 | ||

|

|

ca939fabf7 | ||

|

|

cc3d795bea | ||

|

|

7fc1bac54b | ||

|

|

27367df90c | ||

|

|

f93861e321 | ||

|

|

30e56ec835 | ||

|

|

48ccef9ad2 | ||

|

|

b79e002635 | ||

|

|

1fa28b7cb6 | ||

|

|

22f7eae3f2 | ||

|

|

ae93773465 | ||

|

|

0f387553d1 | ||

|

|

d53a253c8d | ||

|

|

f8f0a6e462 | ||

|

|

f7eea768f6 | ||

|

|

53d316f706 | ||

|

|

741de7f927 | ||

|

|

16b3669adf | ||

|

|

c5807fdaa4 | ||

|

|

897b7d1b99 | ||

|

|

409264960e | ||

|

|

cfb72eec5a | ||

|

|

778822bd9a | ||

|

|

cfd2c3017f | ||

|

|

caed37a08f | ||

|

|

4c1b54e209 | ||

|

|

e4f0947821 | ||

|

|

22e858f65c | ||

|

|

046d6b7fa0 | ||

|

|

89f36371b9 | ||

|

|

406b3ac805 | ||

|

|

f71ba8885e | ||

|

|

121e87b3e0 | ||

|

|

2d013b8340 | ||

|

|

761e5ff01d | ||

|

|

9812684178 | ||

|

|

f7a87cd6ba | ||

|

|

f67bc3ffe8 | ||

|

|

dff644abe0 | ||

|

|

fc7b4ab880 | ||

|

|

1d0f909ca5 | ||

|

|

a0cdbe449b | ||

|

|

44bd64d797 | ||

|

|

bfa78db458 | ||

|

|

4e77737a3f | ||

|

|

d03c197c80 | ||

|

|

06e42a4e5d | ||

|

|

bd1e85a8d3 | ||

|

|

506d5dce39 | ||

|

|

a7b4c73663 | ||

|

|

d4f3ca1c1b | ||

|

|

471d703611 | ||

|

|

a46bbc54cd | ||

|

|

a4405bbed2 | ||

|

|

e9b189e9f2 | ||

|

|

483bce3ae1 | ||

|

|

7372f6ba11 | ||

|

|

8d92557e53 | ||

|

|

c56342bf79 | ||

|

|

07e094fd50 | ||

|

|

1cc30de32f | ||

|

|

3397d4d69a | ||

|

|

766157bfb4 | ||

|

|

d96223460b | ||

|

|

fd99dfc95b | ||

|

|

10fb7ace04 | ||

|

|

a1a19b103c | ||

|

|

5c111caf40 | ||

|

|

651ee5e4d2 | ||

|

|

c398ac87d9 | ||

|

|

0a77c613b0 | ||

|

|

70bc469373 | ||

|

|

b76334f544 | ||

|

|

14b467db06 | ||

|

|

3a0c22ce7d | ||

|

|

3b7e4e0544 | ||

|

|

d4d5b21b2e | ||

|

|

6e1cd45a46 | ||

|

|

b86d130eb6 | ||

|

|

90afc72e64 | ||

|

|

042c697b6b | ||

|

|

02441ff031 | ||

|

|

210af1fd3d | ||

|

|

06eaa32bf0 | ||

|

|

4f88a5fddb | ||

|

|

eb6be1d725 | ||

|

|

1d99681fd4 | ||

|

|

618be44023 | ||

|

|

544afaff97 | ||

|

|

e6b3b994be | ||

|

|

67f148ff83 | ||

|

|

6c34600599 | ||

|

|

016a4b7491 | ||

|

|

be21b74ad5 | ||

|

|

0f152b4e97 | ||

|

|

0d165d1efa | ||

|

|

9d54215a3a | ||

|

|

8ab916baed | ||

|

|

c83c50b27d | ||

|

|

c2ad214a84 | ||

|

|

459f0e11e5 | ||

|

|

56e43ba204 | ||

|

|

10485cad5a | ||

|

|

53a7798e58 | ||

|

|

372ed58677 | ||

|

|

3f8bfd62b7 | ||

|

|

02a6fcad98 | ||

|

|

651ced68bf | ||

|

|

670b64360d | ||

|

|

1f53fef70a | ||

|

|

d1f067dc5b | ||

|

|

15241b53a8 | ||

|

|

38fd8a674b | ||

|

|

bd37d8d04f | ||

|

|

bc99ad0ad1 | ||

|

|

aea04ee32e | ||

|

|

869c7389e2 | ||

|

|

2738df3801 | ||

|

|

433d7862ea | ||

|

|

7625e1e386 | ||

|

|

53e773a2e1 | ||

|

|

c13b54ad0e | ||

|

|

71c2abb41d | ||

|

|

6205935323 | ||

|

|

5fd5b6e72d | ||

|

|

faf88cea0b | ||

|

|

025b38df40 | ||

|

|

ac60cba75f | ||

|

|

94ee932351 | ||

|

|

cf760d6802 | ||

|

|

c65fdc4bed | ||

|

|

0ac9b3ee5c | ||

|

|

f2bd2c44e2 | ||

|

|

f0beab1778 | ||

|

|

95f2dc065e | ||

|

|

4e8080f290 | ||

|

|

fbbed6fe81 | ||

|

|

2d5a5d0d9e | ||

|

|

d4ddf4e62a | ||

|

|

cb25dab986 | ||

|

|

7aa1628336 | ||

|

|

1dbd3d7aa7 | ||

|

|

24e73e01c7 | ||

|

|

e26f94018c | ||

|

|

1ce67887b9 | ||

|

|

8e0200607f | ||

|

|

bd407ca705 | ||

|

|

48b5ef1681 | ||

|

|

afad59dfbb | ||

|

|

0f9be1d2e7 | ||

|

|

48c2406495 | ||

|

|

9958d93120 | ||

|

|

b63512cd92 | ||

|

|

74c4d1c1db | ||

|

|

7ccd81f706 | ||

|

|

1da8d3f1e6 | ||

|

|

92016da962 | ||

|

|

9c3c9b6e78 | ||

|

|

687871e46a | ||

|

|

3c1803897f | ||

|

|

1c3289f115 | ||

|

|

35d41adc7b | ||

|

|

9a3dd91030 | ||

|

|

017eae63b1 | ||

|

|

8af4454251 | ||

|

|

adf252768c | ||

|

|

3705bdefd5 | ||

|

|

25e94d6344 | ||

|

|

26c345b766 | ||

|

|

9ce50b4684 | ||

|

|

66954c7ded | ||

|

|

e0c3519b94 | ||

|

|

d91b2b3ee8 | ||

|

|

1623b26855 | ||

|

|

9573130630 | ||

|

|

2e0a102565 | ||

|

|

636ce6b3f7 | ||

|

|

1fd1e8733a | ||

|

|

44b45caf65 | ||

|

|

e6da96fbb7 | ||

|

|

c425509d57 | ||

|

|

d8451f75a4 | ||

|

|

a448bd63bd | ||

|

|

27fb2b358c | ||

|

|

68723d5291 | ||

|

|

70bdade23b | ||

|

|

4f964939a1 | ||

|

|

55afb70b37 | ||

|

|

b307d38897 | ||

|

|

a085898309 | ||

|

|

3b40c557ce | ||

|

|

75a07f24bf | ||

|

|

7cea84b74c | ||

|

|

3a5158a784 | ||

|

|

bd581c5337 | ||

|

|

22982287ff | ||

|

|

a41a729682 | ||

|

|

174e7b1730 | ||

|

|

874d24181e | ||

|

|

5db99a27cf | ||

|

|

180b842a1e | ||

|

|

3f53deebc9 | ||

|

|

e5d7878856 | ||

|

|

3eca945bd1 | ||

|

|

ba9c9a3f78 |

1

.github/FUNDING.yml

vendored

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

github: [tiangolo]

|

||||

2

.github/ISSUE_TEMPLATE/question.md

vendored

@@ -21,4 +21,4 @@ Is it possible to [...]?

|

||||

|

||||

### Additional context

|

||||

|

||||

Add any other context or screenshots about the feature request here.

|

||||

Add any other context or screenshots about the question here.

|

||||

|

||||

29

.github/workflows/deploy-docs.yml

vendored

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

name: Build and Deploy to Netlify

|

||||

on:

|

||||

push:

|

||||

pull_request:

|

||||

types: [opened, synchronize]

|

||||

jobs:

|

||||

build:

|

||||

runs-on: ubuntu-18.04

|

||||

steps:

|

||||

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

|

||||

- name: Set up Python

|

||||

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

|

||||

with:

|

||||

python-version: "3.7"

|

||||

- name: Install Flit

|

||||

run: python3.7 -m pip install flit

|

||||

- name: Install docs extras

|

||||

run: python3.7 -m flit install --extras doc

|

||||

- name: Build Docs

|

||||

run: python3.7 ./scripts/docs.py build-all

|

||||

- name: Deploy to Netlify

|

||||

uses: nwtgck/actions-netlify@v1.0.3

|

||||

with:

|

||||

publish-dir: './site'

|

||||

production-branch: master

|

||||

github-token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

|

||||

env:

|

||||

NETLIFY_AUTH_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.NETLIFY_AUTH_TOKEN }}

|

||||

NETLIFY_SITE_ID: ${{ secrets.NETLIFY_SITE_ID }}

|

||||

3

.gitignore

vendored

@@ -13,3 +13,6 @@ coverage.xml

|

||||

test.db

|

||||

log.txt

|

||||

Pipfile.lock

|

||||

env3.*

|

||||

env

|

||||

docs_build

|

||||

|

||||

38

Pipfile

@@ -1,38 +0,0 @@

|

||||

[[source]]

|

||||

name = "pypi"

|

||||

url = "https://pypi.org/simple"

|

||||

verify_ssl = true

|

||||

|

||||

[dev-packages]

|

||||

mypy = "*"

|

||||

black = "*"

|

||||

jupyter = "*"

|

||||

better-exceptions = "*"

|

||||

pytest = "*"

|

||||

pytest-cov = "*"

|

||||

isort = "*"

|

||||

requests = "*"

|

||||

flit = "*"

|

||||

mkdocs = "*"

|

||||

mkdocs-material = "*"

|

||||

markdown-include = "*"

|

||||

autoflake = "*"

|

||||

email-validator = "*"

|

||||

ujson = "*"

|

||||

flake8 = "*"

|

||||

python-multipart = "*"

|

||||

sqlalchemy = "*"

|

||||

uvicorn = "*"

|

||||

|

||||

[packages]

|

||||

starlette = "==0.12.9"

|

||||

pydantic = "==1.0.0"

|

||||

databases = {extras = ["sqlite"],version = "*"}

|

||||

hypercorn = "*"

|

||||

orjson = "*"

|

||||

|

||||

[requires]

|

||||

python_version = "3.6"

|

||||

|

||||

[pipenv]

|

||||

allow_prereleases = true

|

||||

90

README.md

@@ -9,7 +9,7 @@

|

||||

<img src="https://travis-ci.com/tiangolo/fastapi.svg?branch=master" alt="Build Status">

|

||||

</a>

|

||||

<a href="https://codecov.io/gh/tiangolo/fastapi" target="_blank">

|

||||

<img src="https://codecov.io/gh/tiangolo/fastapi/branch/master/graph/badge.svg" alt="Coverage">

|

||||

<img src="https://img.shields.io/codecov/c/github/tiangolo/fastapi" alt="Coverage">

|

||||

</a>

|

||||

<a href="https://pypi.org/project/fastapi" target="_blank">

|

||||

<img src="https://badge.fury.io/py/fastapi.svg" alt="Package version">

|

||||

@@ -33,13 +33,13 @@ The key features are:

|

||||

|

||||

* **Fast**: Very high performance, on par with **NodeJS** and **Go** (thanks to Starlette and Pydantic). [One of the fastest Python frameworks available](#performance).

|

||||

|

||||

* **Fast to code**: Increase the speed to develop features by about 200% to 300% *.

|

||||

* **Fast to code**: Increase the speed to develop features by about 200% to 300%. *

|

||||

* **Fewer bugs**: Reduce about 40% of human (developer) induced errors. *

|

||||

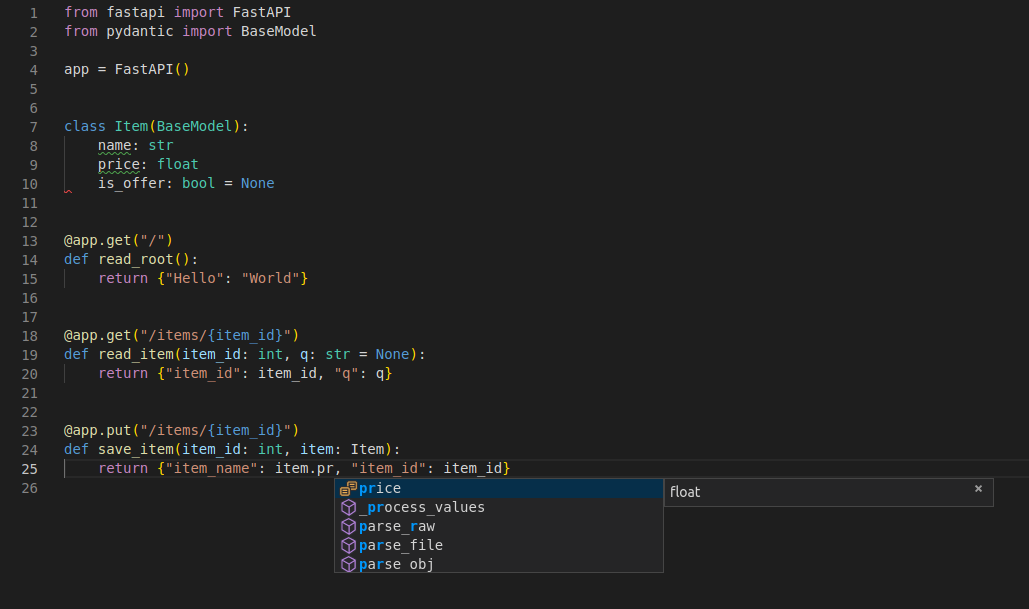

* **Intuitive**: Great editor support. <abbr title="also known as auto-complete, autocompletion, IntelliSense">Completion</abbr> everywhere. Less time debugging.

|

||||

* **Easy**: Designed to be easy to use and learn. Less time reading docs.

|

||||

* **Short**: Minimize code duplication. Multiple features from each parameter declaration. Fewer bugs.

|

||||

* **Robust**: Get production-ready code. With automatic interactive documentation.

|

||||

* **Standards-based**: Based on (and fully compatible with) the open standards for APIs: <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification" target="_blank">OpenAPI</a> (previously known as Swagger) and <a href="http://json-schema.org/" target="_blank">JSON Schema</a>.

|

||||

* **Standards-based**: Based on (and fully compatible with) the open standards for APIs: <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI</a> (previously known as Swagger) and <a href="http://json-schema.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">JSON Schema</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

<small>* estimation based on tests on an internal development team, building production applications.</small>

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -77,28 +77,47 @@ The key features are:

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

## **Typer**, the FastAPI of CLIs

|

||||

|

||||

<a href="https://typer.tiangolo.com" target="_blank"><img src="https://typer.tiangolo.com/img/logo-margin/logo-margin-vector.svg" style="width: 20%;"></a>

|

||||

|

||||

If you are building a <abbr title="Command Line Interface">CLI</abbr> app to be used in the terminal instead of a web API, check out <a href="https://typer.tiangolo.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">**Typer**</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

**Typer** is FastAPI's little sibling. And it's intended to be the **FastAPI of CLIs**. ⌨️ 🚀

|

||||

|

||||

## Requirements

|

||||

|

||||

Python 3.6+

|

||||

|

||||

FastAPI stands on the shoulders of giants:

|

||||

|

||||

* <a href="https://www.starlette.io/" target="_blank">Starlette</a> for the web parts.

|

||||

* <a href="https://pydantic-docs.helpmanual.io/" target="_blank">Pydantic</a> for the data parts.

|

||||

|

||||

* <a href="https://www.starlette.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette</a> for the web parts.

|

||||

* <a href="https://pydantic-docs.helpmanual.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic</a> for the data parts.

|

||||

|

||||

## Installation

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

pip install fastapi

|

||||

<div class="termy">

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ pip install fastapi

|

||||

|

||||

---> 100%

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You will also need an ASGI server, for production such as <a href="http://www.uvicorn.org" target="_blank">Uvicorn</a> or <a href="https://gitlab.com/pgjones/hypercorn" target="_blank">Hypercorn</a>.

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

pip install uvicorn

|

||||

You will also need an ASGI server, for production such as <a href="http://www.uvicorn.org" class="external-link" target="_blank">Uvicorn</a> or <a href="https://gitlab.com/pgjones/hypercorn" class="external-link" target="_blank">Hypercorn</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

<div class="termy">

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ pip install uvicorn

|

||||

|

||||

---> 100%

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

## Example

|

||||

|

||||

### Create it

|

||||

@@ -120,6 +139,7 @@ def read_root():

|

||||

def read_item(item_id: int, q: str = None):

|

||||

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

<details markdown="1">

|

||||

<summary>Or use <code>async def</code>...</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -142,7 +162,7 @@ async def read_item(item_id: int, q: str = None):

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

**Note**:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

If you don't know, check the _"In a hurry?"_ section about <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/async/#in-a-hurry" target="_blank">`async` and `await` in the docs</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

</details>

|

||||

@@ -151,10 +171,20 @@ If you don't know, check the _"In a hurry?"_ section about <a href="https://fast

|

||||

|

||||

Run the server with:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

uvicorn main:app --reload

|

||||

<div class="termy">

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ uvicorn main:app --reload

|

||||

|

||||

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

|

||||

INFO: Started reloader process [28720]

|

||||

INFO: Started server process [28722]

|

||||

INFO: Waiting for application startup.

|

||||

INFO: Application startup complete.

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

<details markdown="1">

|

||||

<summary>About the command <code>uvicorn main:app --reload</code>...</summary>

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -168,7 +198,7 @@ The command `uvicorn main:app` refers to:

|

||||

|

||||

### Check it

|

||||

|

||||

Open your browser at <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery</a>.

|

||||

Open your browser at <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

You will see the JSON response as:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -185,18 +215,17 @@ You already created an API that:

|

||||

|

||||

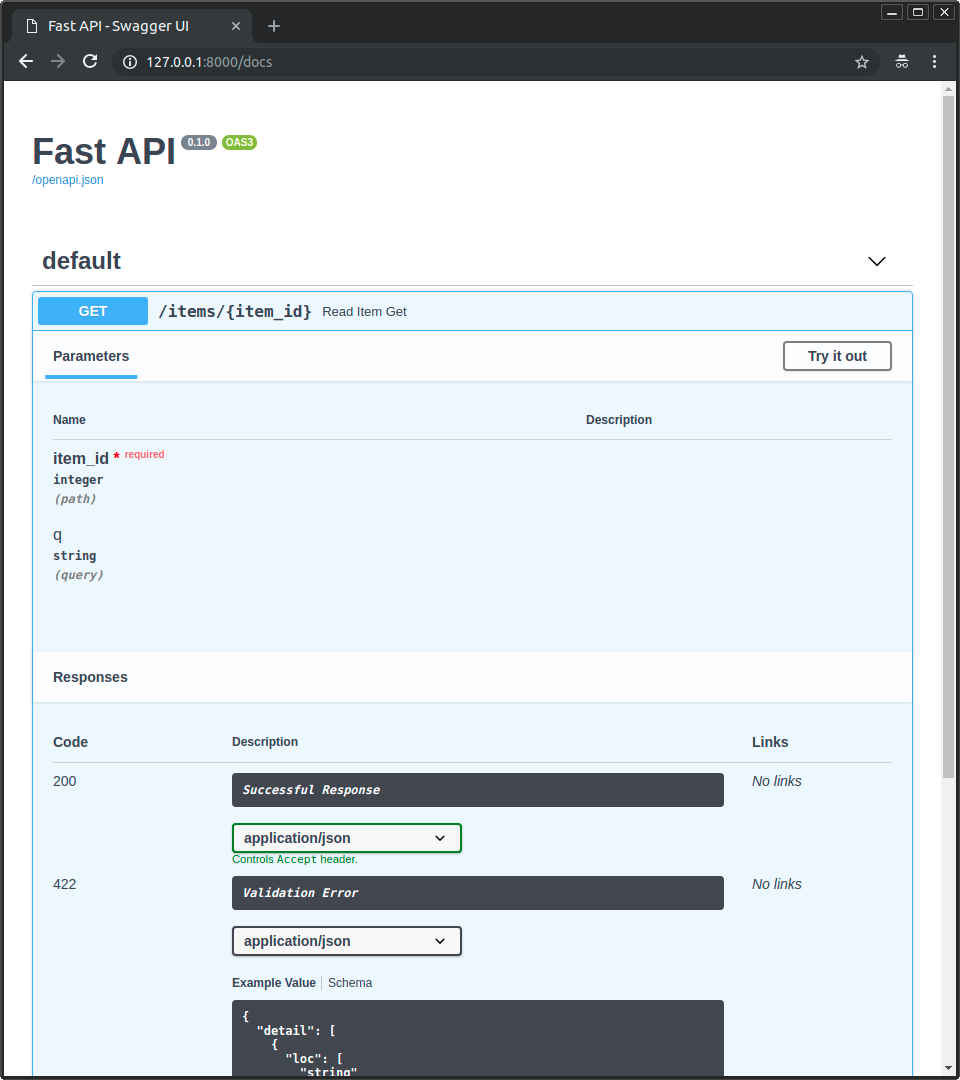

### Interactive API docs

|

||||

|

||||

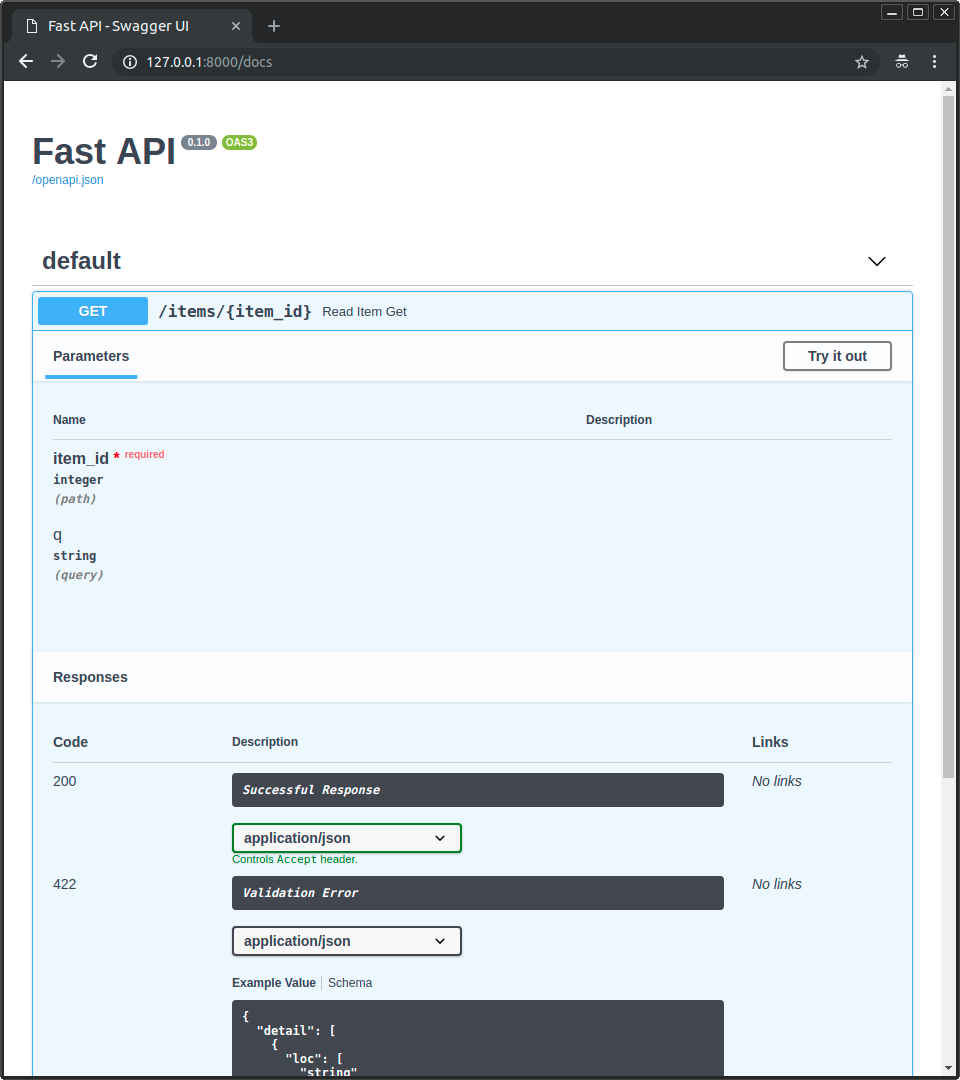

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

You will see the automatic interactive API documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/swagger-api/swagger-ui" target="_blank">Swagger UI</a>):

|

||||

You will see the automatic interactive API documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/swagger-api/swagger-ui" class="external-link" target="_blank">Swagger UI</a>):

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

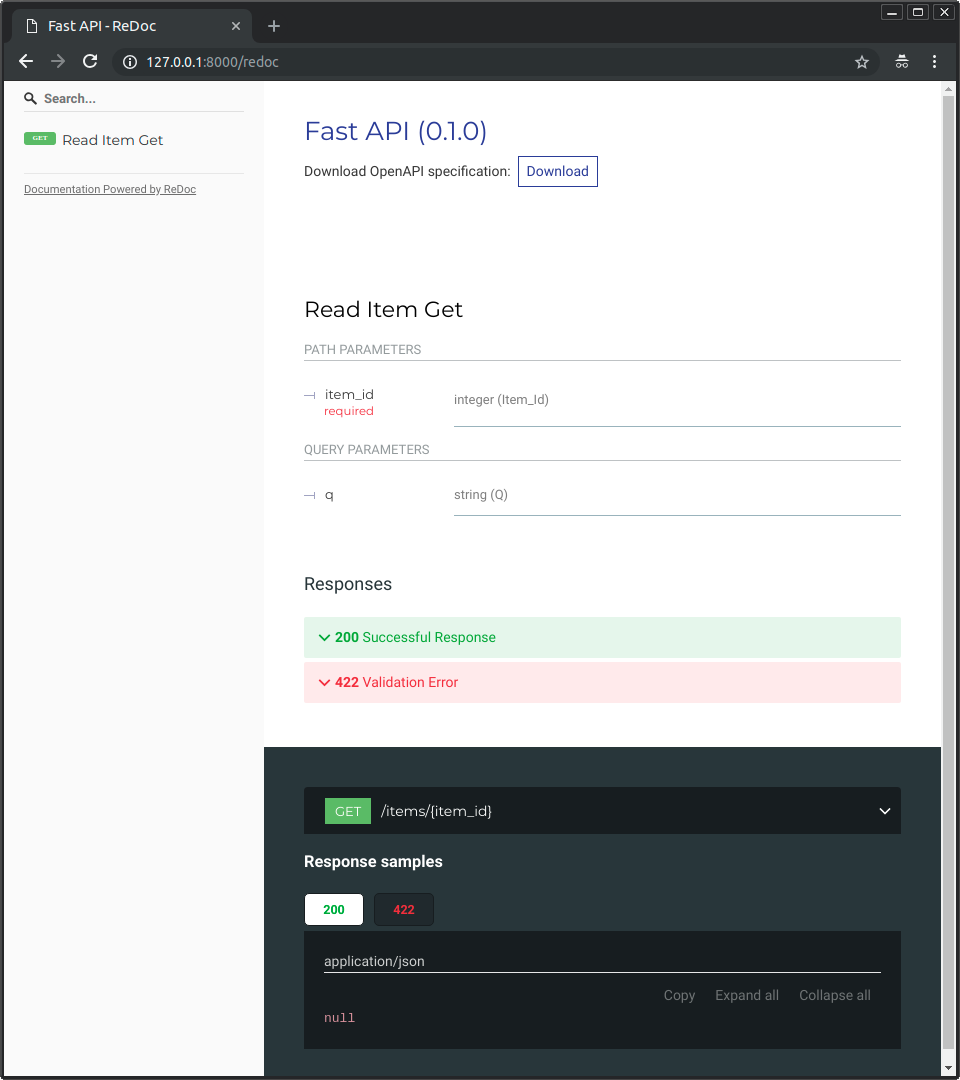

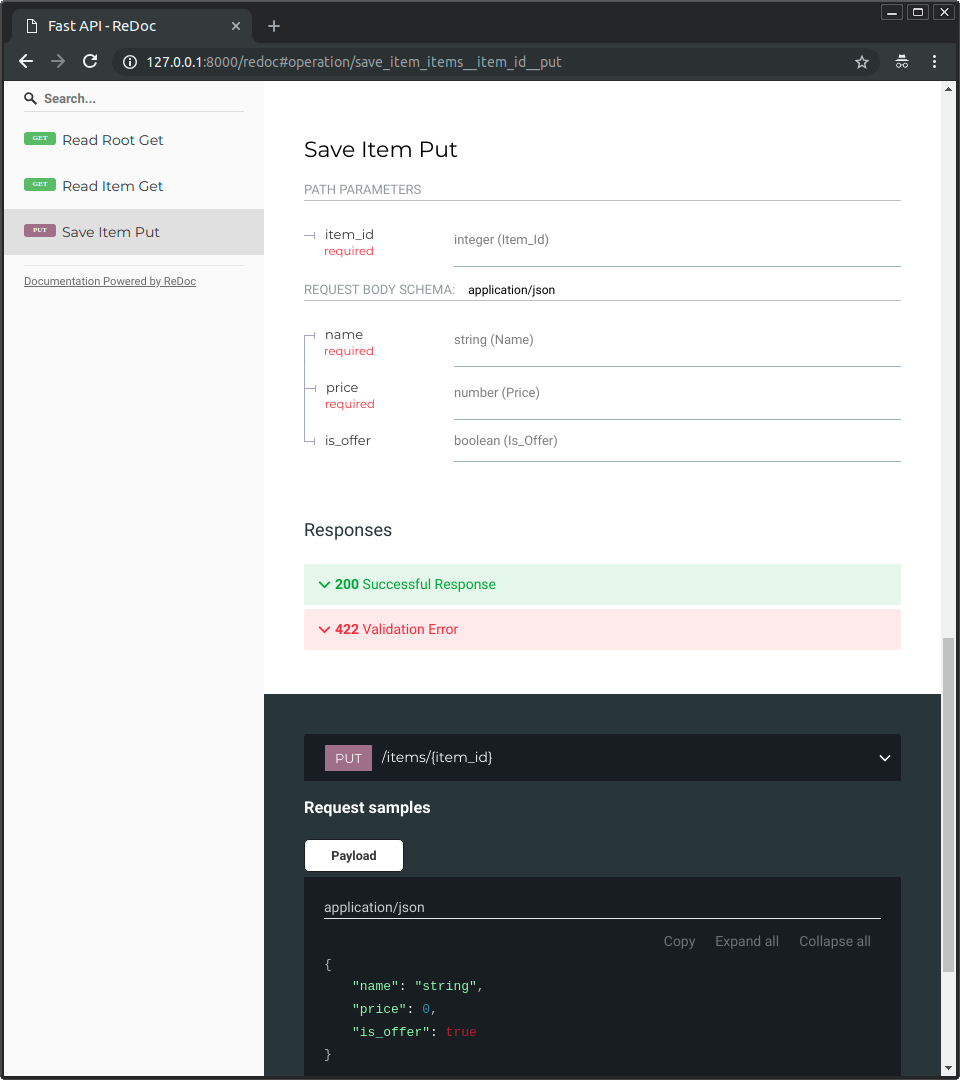

### Alternative API docs

|

||||

|

||||

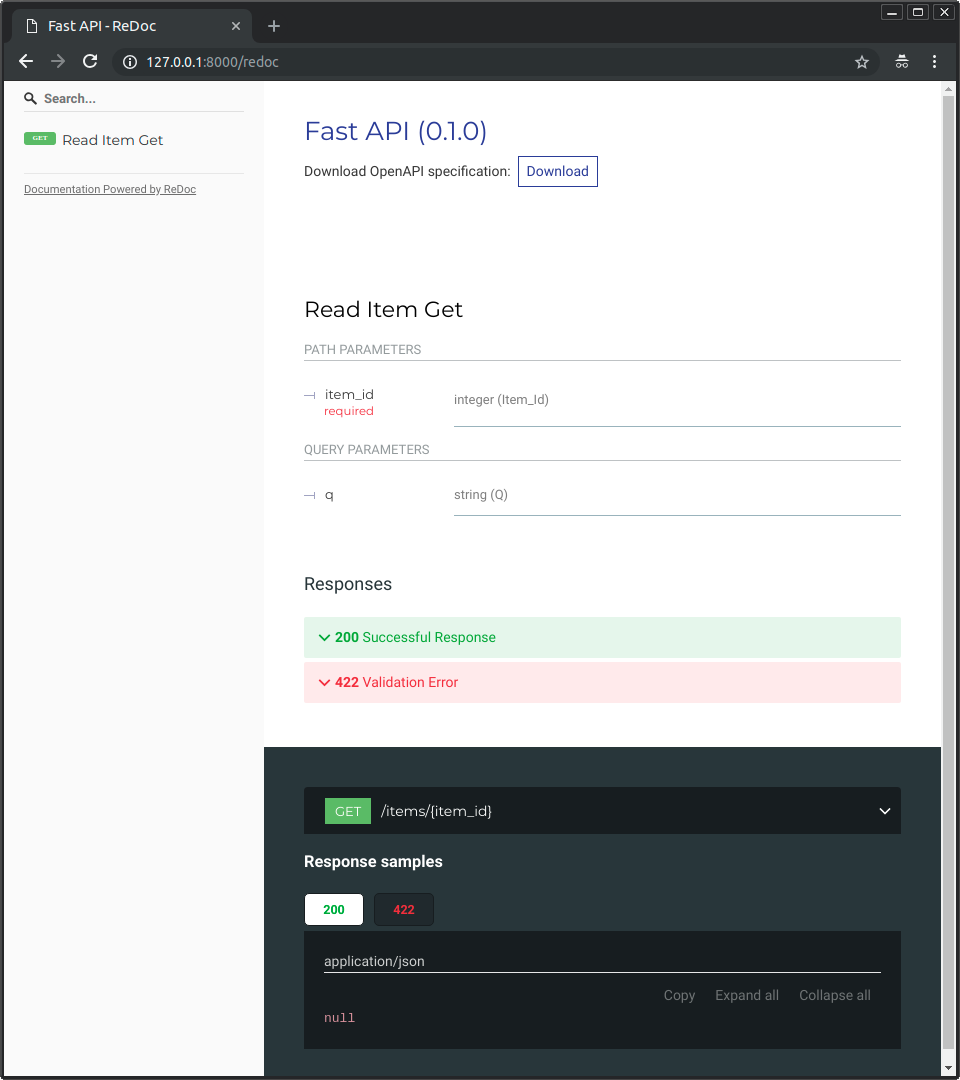

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

|

||||

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

You will see the alternative automatic documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/Rebilly/ReDoc" target="_blank">ReDoc</a>):

|

||||

You will see the alternative automatic documentation (provided by <a href="https://github.com/Rebilly/ReDoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">ReDoc</a>):

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -238,7 +267,7 @@ The server should reload automatically (because you added `--reload` to the `uvi

|

||||

|

||||

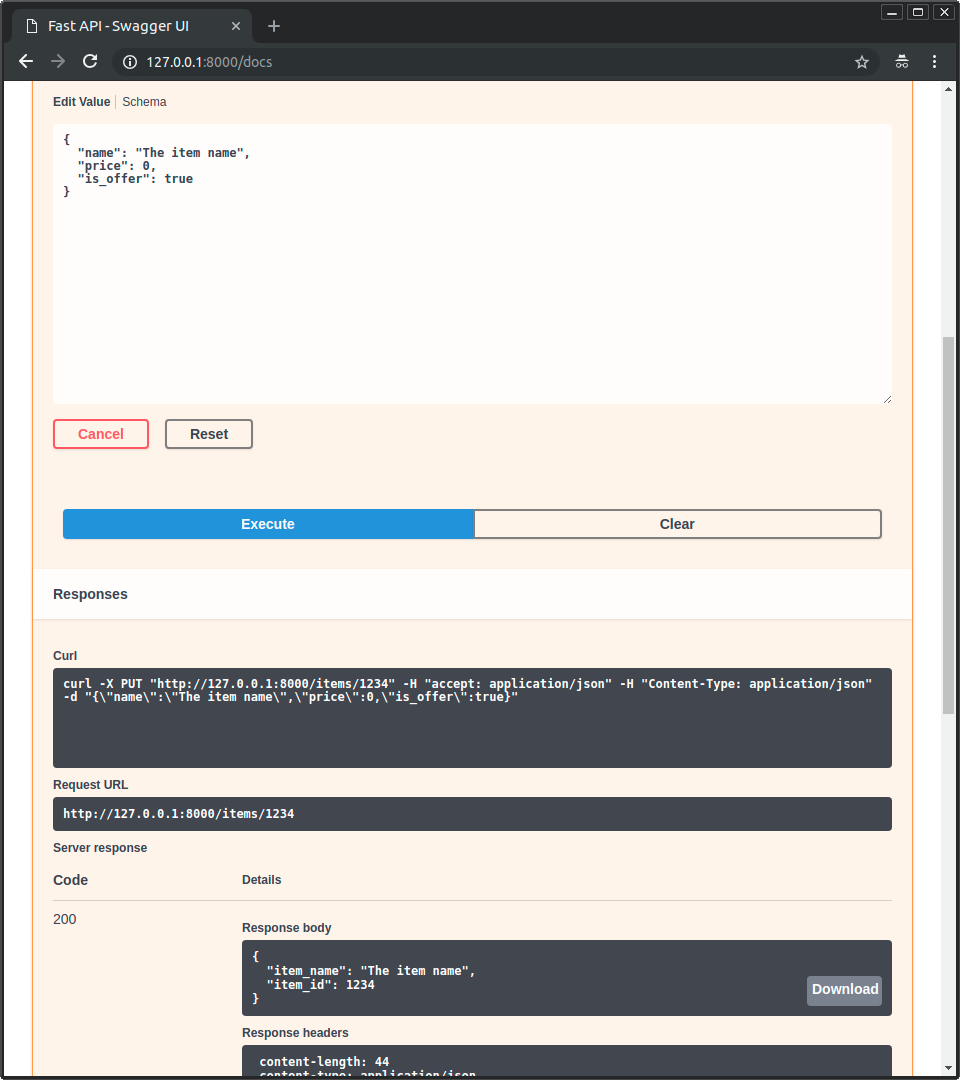

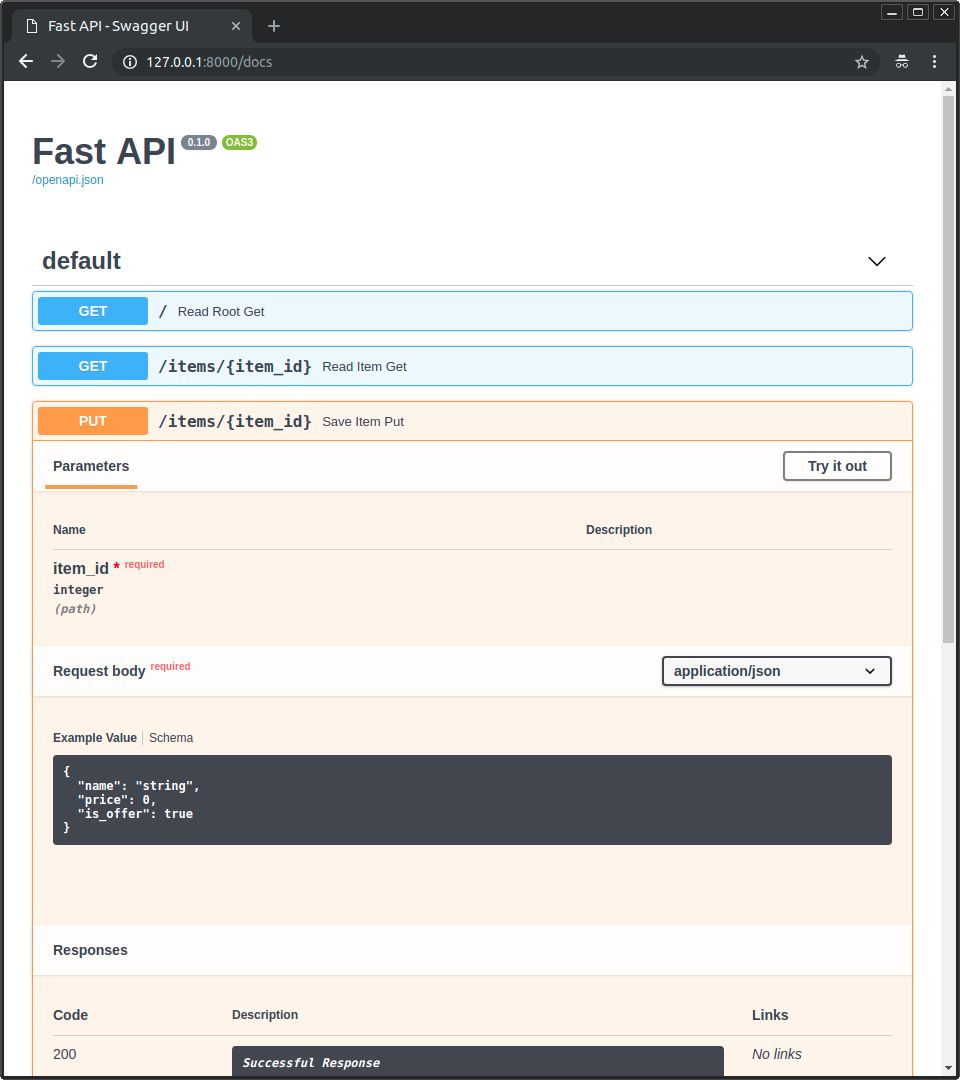

### Interactive API docs upgrade

|

||||

|

||||

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

* The interactive API documentation will be automatically updated, including the new body:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -252,16 +281,14 @@ Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Alternative API docs upgrade

|

||||

|

||||

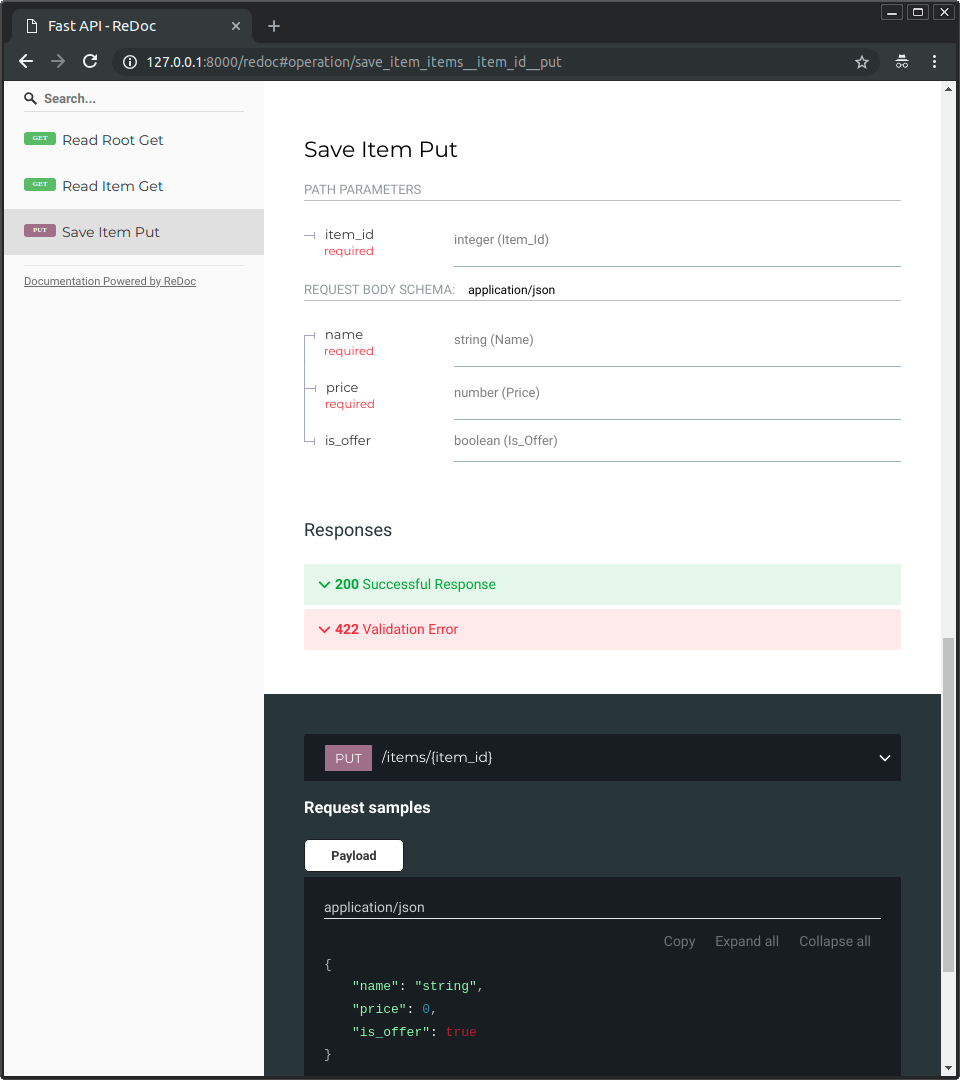

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

|

||||

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

* The alternative documentation will also reflect the new query parameter and body:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Recap

|

||||

|

||||

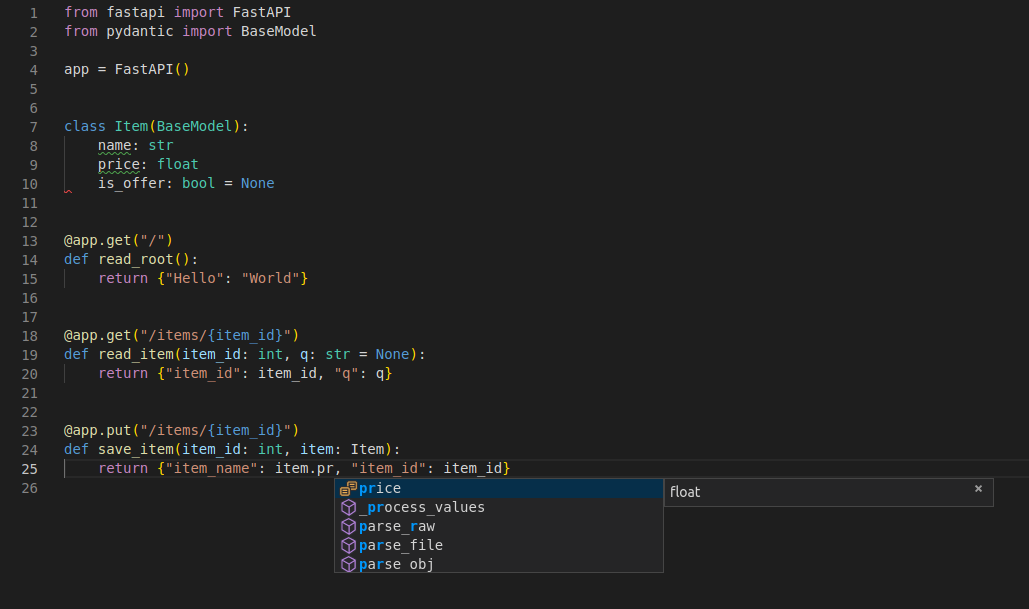

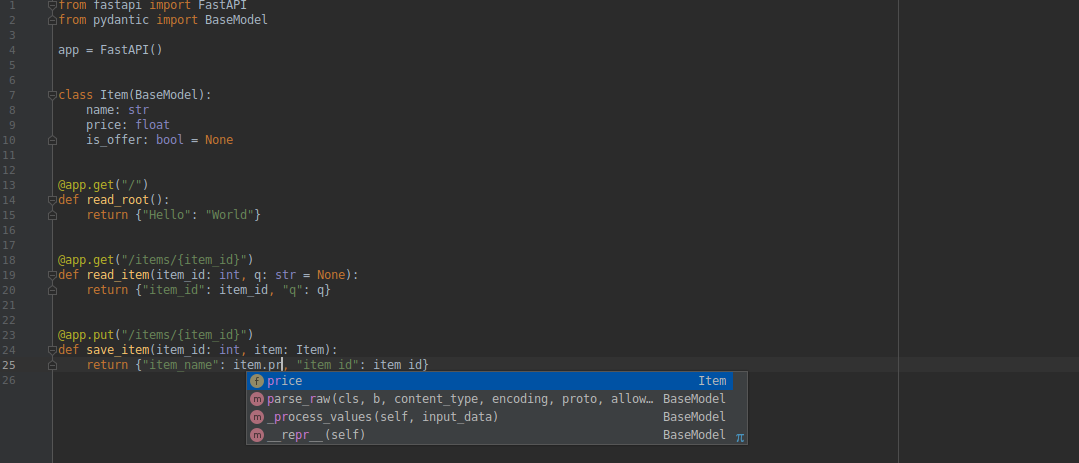

In summary, you declare **once** the types of parameters, body, etc. as function parameters.

|

||||

@@ -322,7 +349,7 @@ Coming back to the previous code example, **FastAPI** will:

|

||||

* Without the `None` it would be required (as is the body in the case with `PUT`).

|

||||

* For `PUT` requests to `/items/{item_id}`, Read the body as JSON:

|

||||

* Check that it has a required attribute `name` that should be a `str`.

|

||||

* Check that is has a required attribute `price` that has to be a `float`.

|

||||

* Check that it has a required attribute `price` that has to be a `float`.

|

||||

* Check that it has an optional attribute `is_offer`, that should be a `bool`, if present.

|

||||

* All this would also work for deeply nested JSON objects.

|

||||

* Convert from and to JSON automatically.

|

||||

@@ -331,7 +358,6 @@ Coming back to the previous code example, **FastAPI** will:

|

||||

* Automatic client code generation systems, for many languages.

|

||||

* Provide 2 interactive documentation web interfaces directly.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

We just scratched the surface, but you already get the idea of how it all works.

|

||||

@@ -358,8 +384,7 @@ Try changing the line with:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

For a more complete example including more features, see the <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/tutorial/intro/">Tutorial - User Guide</a>.

|

||||

For a more complete example including more features, see the <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/tutorial/">Tutorial - User Guide</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

**Spoiler alert**: the tutorial - user guide includes:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -376,12 +401,11 @@ For a more complete example including more features, see the <a href="https://fa

|

||||

* **Cookie Sessions**

|

||||

* ...and more.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Performance

|

||||

|

||||

Independent TechEmpower benchmarks show **FastAPI** applications running under Uvicorn as <a href="https://www.techempower.com/benchmarks/#section=test&runid=7464e520-0dc2-473d-bd34-dbdfd7e85911&hw=ph&test=query&l=zijzen-7" target="_blank">one of the fastest Python frameworks available</a>, only below Starlette and Uvicorn themselves (used internally by FastAPI). (*)

|

||||

Independent TechEmpower benchmarks show **FastAPI** applications running under Uvicorn as <a href="https://www.techempower.com/benchmarks/#section=test&runid=7464e520-0dc2-473d-bd34-dbdfd7e85911&hw=ph&test=query&l=zijzen-7" class="external-link" target="_blank">one of the fastest Python frameworks available</a>, only below Starlette and Uvicorn themselves (used internally by FastAPI). (*)

|

||||

|

||||

To understand more about it, see the section <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/benchmarks/" target="_blank">Benchmarks</a>.

|

||||

To understand more about it, see the section <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/benchmarks/" class="internal-link" target="_blank">Benchmarks</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

## Optional Dependencies

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -390,7 +414,6 @@ Used by Pydantic:

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/esnme/ultrajson" target="_blank"><code>ujson</code></a> - for faster JSON <abbr title="converting the string that comes from an HTTP request into Python data">"parsing"</abbr>.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/JoshData/python-email-validator" target="_blank"><code>email_validator</code></a> - for email validation.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Used by Starlette:

|

||||

|

||||

* <a href="http://docs.python-requests.org" target="_blank"><code>requests</code></a> - Required if you want to use the `TestClient`.

|

||||

@@ -398,13 +421,14 @@ Used by Starlette:

|

||||

* <a href="http://jinja.pocoo.org" target="_blank"><code>jinja2</code></a> - Required if you want to use the default template configuration.

|

||||

* <a href="https://andrew-d.github.io/python-multipart/" target="_blank"><code>python-multipart</code></a> - Required if you want to support form <abbr title="converting the string that comes from an HTTP request into Python data">"parsing"</abbr>, with `request.form()`.

|

||||

* <a href="https://pythonhosted.org/itsdangerous/" target="_blank"><code>itsdangerous</code></a> - Required for `SessionMiddleware` support.

|

||||

* <a href="https://pyyaml.org/wiki/PyYAMLDocumentation" target="_blank"><code>pyyaml</code></a> - Required for `SchemaGenerator` support.

|

||||

* <a href="https://pyyaml.org/wiki/PyYAMLDocumentation" target="_blank"><code>pyyaml</code></a> - Required for Starlette's `SchemaGenerator` support (you probably don't need it with FastAPI).

|

||||

* <a href="https://graphene-python.org/" target="_blank"><code>graphene</code></a> - Required for `GraphQLApp` support.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/esnme/ultrajson" target="_blank"><code>ujson</code></a> - Required if you want to use `UJSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

Used by FastAPI / Starlette:

|

||||

|

||||

* <a href="http://www.uvicorn.org" target="_blank"><code>uvicorn</code></a> - for the server that loads and serves your application.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" target="_blank"><code>orjson</code></a> - Required if you want to use `ORJSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

You can install all of these with `pip install fastapi[all]`.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -1,123 +0,0 @@

|

||||

First, you might want to see the basic ways to <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/help-fastapi/" target="_blank">help FastAPI and get help</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

## Developing

|

||||

|

||||

If you already cloned the repository and you know that you need to deep dive in the code, here are some guidelines to set up your environment.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Pipenv

|

||||

|

||||

If you are using <a href="https://pipenv.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" target="_blank">Pipenv</a>, you can create a virtual environment and install the packages with:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

pipenv install --dev

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then you can activate that virtual environment with:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

pipenv shell

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### No Pipenv

|

||||

|

||||

If you are not using Pipenv, you can create a virtual environment with your preferred tool, and install the packages listed in the file `Pipfile`.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Flit

|

||||

|

||||

**FastAPI** uses <a href="https://flit.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html" target="_blank">Flit</a> to build, package and publish the project.

|

||||

|

||||

If you installed the development dependencies with one of the methods above, you already have the `flit` command.

|

||||

|

||||

To install your local version of FastAPI as a package in your local environment, run:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

flit install --symlink

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It will install your local FastAPI in your local environment.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Using your local FastAPI

|

||||

|

||||

If you create a Python file that imports and uses FastAPI, and run it with the Python from your local environment, it will use your local FastAPI source code.

|

||||

|

||||

And if you update that local FastAPI source code, as it is installed with `--symlink`, when you run that Python file again, it will use the fresh version of FastAPI you just edited.

|

||||

|

||||

That way, you don't have to "install" your local version to be able to test every change.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Format

|

||||

|

||||

There is a script that you can run that will format and clean all your code:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

bash scripts/lint.sh

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It will also auto-sort all your imports.

|

||||

|

||||

For it to sort them correctly, you need to have FastAPI installed locally in your environment, with the command in the section above:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

flit install --symlink

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Docs

|

||||

|

||||

The documentation uses <a href="https://www.mkdocs.org/" target="_blank">MkDocs</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

All the documentation is in Markdown format in the directory `./docs`.

|

||||

|

||||

Many of the tutorials have blocks of code.

|

||||

|

||||

In most of the cases, these blocks of code are actual complete applications that can be run as is.

|

||||

|

||||

In fact, those blocks of code are not written inside the Markdown, they are Python files in the `./docs/src/` directory.

|

||||

|

||||

And those Python files are included/injected in the documentation when generating the site.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Docs for tests

|

||||

|

||||

Most of the tests actually run against the example source files in the documentation.

|

||||

|

||||

This helps making sure that:

|

||||

|

||||

* The documentation is up to date.

|

||||

* The documentation examples can be run as is.

|

||||

* Most of the features are covered by the documentation, ensured by the coverage tests.

|

||||

|

||||

During local development, there is a script that builds the site and checks for any changes, live-reloading:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

bash scripts/docs-live.sh

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It will serve the documentation on `http://0.0.0.0:8008`.

|

||||

|

||||

That way, you can edit the documentation/source files and see the changes live.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Apps and docs at the same time

|

||||

|

||||

And if you run the examples with, e.g.:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

uvicorn tutorial001:app --reload

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

as Uvicorn by default will use the port `8000`, the documentation on port `8008` won't clash.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Tests

|

||||

|

||||

There is a script that you can run locally to test all the code and generate coverage reports in HTML:

|

||||

|

||||

```bash

|

||||

bash scripts/test-cov-html.sh

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This command generates a directory `./htmlcov/`, if you open the file `./htmlcov/index.html` in your browser, you can explore interactively the regions of code that are covered by the tests, and notice if there is any region missing.

|

||||

@@ -1,6 +1,8 @@

|

||||

# Additional Responses in OpenAPI

|

||||

|

||||

!!! warning

|

||||

This is a rather advanced topic.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

If you are starting with **FastAPI**, you might not need this.

|

||||

|

||||

You can declare additional responses, with additional status codes, media types, descriptions, etc.

|

||||

@@ -21,9 +23,8 @@ Each of those response `dict`s can have a key `model`, containing a Pydantic mod

|

||||

|

||||

For example, to declare another response with a status code `404` and a Pydantic model `Message`, you can write:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="18 23"

|

||||

{!./src/additional_responses/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/additional_responses/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note

|

||||

@@ -168,7 +169,7 @@ You can use this same `responses` parameter to add different media types for the

|

||||

For example, you can add an additional media type of `image/png`, declaring that your *path operation* can return a JSON object (with media type `application/json`) or a PNG image:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 28"

|

||||

{!./src/additional_responses/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/additional_responses/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note

|

||||

@@ -192,14 +193,13 @@ For example, you can declare a response with a status code `404` that uses a Pyd

|

||||

And a response with a status code `200` that uses your `response_model`, but includes a custom `example`:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31"

|

||||

{!./src/additional_responses/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/additional_responses/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It will all be combined and included in your OpenAPI, and shown in the API docs:

|

||||

|

||||

<img src="/img/tutorial/additional-responses/image01.png">

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Combine predefined responses and custom ones

|

||||

|

||||

You might want to have some predefined responses that apply to many *path operations*, but you want to combine them with custom responses needed by each *path operation*.

|

||||

@@ -229,12 +229,12 @@ You can use that technique to re-use some predefined responses in your *path ope

|

||||

For example:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="11 12 13 14 15 24"

|

||||

{!./src/additional_responses/tutorial004.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/additional_responses/tutorial004.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## More information about OpenAPI responses

|

||||

|

||||

To see what exactly you can include in the responses, you can check these sections in the OpenAPI specification:

|

||||

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.0.2.md#responsesObject" target="_blank">OpenAPI Responses Object</a>, it includes the `Response Object`.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.0.2.md#responseObject" target="_blank">OpenAPI Response Object</a>, you can include anything from this directly in each response inside your `responses` parameter. Including `description`, `headers`, `content` (inside of this is that you declare different media types and JSON Schemas), and `links`.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.0.2.md#responsesObject" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI Responses Object</a>, it includes the `Response Object`.

|

||||

* <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.0.2.md#responseObject" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI Response Object</a>, you can include anything from this directly in each response inside your `responses` parameter. Including `description`, `headers`, `content` (inside of this is that you declare different media types and JSON Schemas), and `links`.

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,6 @@

|

||||

By default, **FastAPI** will return the responses using Starlette's `JSONResponse`, putting the content you return from your *path operation* inside of that `JSONResponse`.

|

||||

# Additional Status Codes

|

||||

|

||||

By default, **FastAPI** will return the responses using a `JSONResponse`, putting the content you return from your *path operation* inside of that `JSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

It will use the default status code or the one you set in your *path operation*.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -12,8 +14,8 @@ But you also want it to accept new items. And when the items didn't exist before

|

||||

|

||||

To achieve that, import `JSONResponse`, and return your content there directly, setting the `status_code` that you want:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 20"

|

||||

{!./src/additional_status_codes/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 19"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/additional_status_codes/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! warning

|

||||

@@ -23,8 +25,13 @@ To achieve that, import `JSONResponse`, and return your content there directly,

|

||||

|

||||

Make sure it has the data you want it to have, and that the values are valid JSON (if you are using `JSONResponse`).

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note "Technical Details"

|

||||

You could also use `from starlette.responses import JSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

**FastAPI** provides the same `starlette.responses` as `fastapi.responses` just as a convenience for you, the developer. But most of the available responses come directly from Starlette. The same with `status`.

|

||||

|

||||

## OpenAPI and API docs

|

||||

|

||||

If you return additional status codes and responses directly, they won't be included in the OpenAPI schema (the API docs), because FastAPI doesn't have a way to know before hand what you are going to return.

|

||||

If you return additional status codes and responses directly, they won't be included in the OpenAPI schema (the API docs), because FastAPI doesn't have a way to know beforehand what you are going to return.

|

||||

|

||||

But you can document that in your code, using: <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/tutorial/additional-responses/" target="_blank">Additional Responses</a>.

|

||||

But you can document that in your code, using: [Additional Responses](additional-responses.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

|

||||

@@ -1,7 +1,4 @@

|

||||

!!! warning

|

||||

This is, more or less, an "advanced" chapter.

|

||||

|

||||

If you are just starting with **FastAPI** you might want to skip this chapter and come back to it later.

|

||||

# Advanced Dependencies

|

||||

|

||||

## Parameterized dependencies

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -22,7 +19,7 @@ Not the class itself (which is already a callable), but an instance of that clas

|

||||

To do that, we declare a method `__call__`:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="10"

|

||||

{!./src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, this `__call__` is what **FastAPI** will use to check for additional parameters and sub-dependencies, and this is what will be called to pass a value to the parameter in your *path operation function* later.

|

||||

@@ -32,7 +29,7 @@ In this case, this `__call__` is what **FastAPI** will use to check for addition

|

||||

And now, we can use `__init__` to declare the parameters of the instance that we can use to "parameterize" the dependency:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="7"

|

||||

{!./src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, **FastAPI** won't ever touch or care about `__init__`, we will use it directly in our code.

|

||||

@@ -42,7 +39,7 @@ In this case, **FastAPI** won't ever touch or care about `__init__`, we will use

|

||||

We could create an instance of this class with:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="16"

|

||||

{!./src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

And that way we are able to "parameterize" our dependency, that now has `"bar"` inside of it, as the attribute `checker.fixed_content`.

|

||||

@@ -57,10 +54,10 @@ And when solving the dependency, **FastAPI** will call this `checker` like:

|

||||

checker(q="somequery")

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

...and pass whatever that returns as the value of the dependency in our path operation function as the parameter `fixed_content_included`:

|

||||

...and pass whatever that returns as the value of the dependency in our *path operation function* as the parameter `fixed_content_included`:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="20"

|

||||

{!./src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/dependencies/tutorial011.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

@@ -68,6 +65,6 @@ checker(q="somequery")

|

||||

|

||||

These examples are intentionally simple, but show how it all works.

|

||||

|

||||

In the chapters about security, you will be using utility functions that are implemented in this same way.

|

||||

In the chapters about security, there are utility functions that are implemented in this same way.

|

||||

|

||||

If you understood all this, you already know how those utility tools for security work underneath.

|

||||

@@ -1,4 +1,6 @@

|

||||

You can also use <a href="https://github.com/encode/databases" target="_blank">`encode/databases`</a> with **FastAPI** to connect to databases using `async` and `await`.

|

||||

# Async SQL (Relational) Databases

|

||||

|

||||

You can also use <a href="https://github.com/encode/databases" class="external-link" target="_blank">`encode/databases`</a> with **FastAPI** to connect to databases using `async` and `await`.

|

||||

|

||||

It is compatible with:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -11,9 +13,9 @@ In this example, we'll use **SQLite**, because it uses a single file and Python

|

||||

Later, for your production application, you might want to use a database server like **PostgreSQL**.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

You could adopt ideas from the previous section about <a href="/tutorial/sql-databases/" target="_blank">SQLAlchemy ORM</a>, like using utility functions to perform operations in the database, independent of your **FastAPI** code.

|

||||

You could adopt ideas from the section about SQLAlchemy ORM ([SQL (Relational) Databases](../tutorial/sql-databases.md){.internal-link target=_blank}), like using utility functions to perform operations in the database, independent of your **FastAPI** code.

|

||||

|

||||

This section doesn't apply those ideas, to be equivalent to the counterpart in <a href="https://www.starlette.io/database/" target="_blank">Starlette</a>.

|

||||

This section doesn't apply those ideas, to be equivalent to the counterpart in <a href="https://www.starlette.io/database/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

## Import and set up `SQLAlchemy`

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -22,7 +24,7 @@ Later, for your production application, you might want to use a database server

|

||||

* Create a table `notes` using the `metadata` object.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="4 14 16 17 18 19 20 21 22"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

@@ -37,7 +39,7 @@ Later, for your production application, you might want to use a database server

|

||||

* Create a `database` object.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="3 9 12"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

@@ -53,7 +55,7 @@ Here, this section would run directly, right before starting your **FastAPI** ap

|

||||

* Create all the tables from the `metadata` object.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="25 26 27 28"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Create models

|

||||

@@ -64,7 +66,7 @@ Create Pydantic models for:

|

||||

* Notes to be returned (`Note`).

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="31 32 33 36 37 38 39"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

By creating these Pydantic models, the input data will be validated, serialized (converted), and annotated (documented).

|

||||

@@ -77,7 +79,7 @@ So, you will be able to see it all in the interactive API docs.

|

||||

* Create event handlers to connect and disconnect from the database.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="42 45 46 47 50 51 52"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Read notes

|

||||

@@ -85,7 +87,7 @@ So, you will be able to see it all in the interactive API docs.

|

||||

Create the *path operation function* to read notes:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="55 56 57 58"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! Note

|

||||

@@ -102,7 +104,7 @@ That documents (and validates, serializes, filters) the output data, as a `list`

|

||||

Create the *path operation function* to create notes:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="61 62 63 64 65"

|

||||

{!./src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/async_sql_databases/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! Note

|

||||

@@ -149,7 +151,7 @@ So, the final result returned would be something like:

|

||||

|

||||

## Check it

|

||||

|

||||

You can copy this code as is, and see the docs at <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

You can copy this code as is, and see the docs at <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

There you can see all your API documented and interact with it:

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -157,4 +159,4 @@ There you can see all your API documented and interact with it:

|

||||

|

||||

## More info

|

||||

|

||||

You can read more about <a href="https://github.com/encode/databases" target="_blank">`encode/databases` at its GitHub page</a>.

|

||||

You can read more about <a href="https://github.com/encode/databases" class="external-link" target="_blank">`encode/databases` at its GitHub page</a>.

|

||||

58

docs/en/docs/advanced/conditional-openapi.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,58 @@

|

||||

# Conditional OpenAPI

|

||||

|

||||

If you needed to, you could use settings and environment variables to configure OpenAPI conditionally depending on the environment, and even disable it entirely.

|

||||

|

||||

## About security, APIs, and docs

|

||||

|

||||

Hiding your documentation user interfaces in production *shouldn't* be the way to protect your API.

|

||||

|

||||

That doesn't add any extra security to your API, the *path operations* will still be available where they are.

|

||||

|

||||

If there's a security flaw in your code, it will still exist.

|

||||

|

||||

Hiding the documentation just makes it more difficult to understand how to interact with your API, and could make it more difficult for you to debug it in production. It could be considered simply a form of <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Security_through_obscurity" class="external-link" target="_blank">Security through obscurity</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to secure your API, there are several better things you can do, for example:

|

||||

|

||||

* Make sure you have well defined Pydantic models for your request bodies and responses.

|

||||

* Configure any required permissions and roles using dependencies.

|

||||

* Never store plaintext passwords, only password hashes.

|

||||

* Implement and use well-known cryptographic tools, like Passlib and JWT tokens, etc.

|

||||

* Add more granular permission controls with OAuth2 scopes where needed.

|

||||

* ...etc.

|

||||

|

||||

Nevertheless, you might have a very specific use case where you really need to disable the API docs for some environment (e.g. for production) or depending on configurations from environment variables.

|

||||

|

||||

## Conditional OpenAPI from settings and env vars

|

||||

|

||||

You can easily use the same Pydantic settings to configure your generated OpenAPI and the docs UIs.

|

||||

|

||||

For example:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="6 11"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/conditional_openapi/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Here we declare the setting `openapi_url` with the same default of `"/openapi.json"`.

|

||||

|

||||

And then we use it when creating the `FastAPI` app.

|

||||

|

||||

Then you could disable OpenAPI (including the UI docs) by setting the environment variable `OPENAPI_URL` to the empty string, like:

|

||||

|

||||

<div class="termy">

|

||||

|

||||

```console

|

||||

$ OPENAPI_URL= uvicorn main:app

|

||||

|

||||

<span style="color: green;">INFO</span>: Uvicorn running on http://127.0.0.1:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

Then if you go to the URLs at `/openapi.json`, `/docs`, or `/redoc` you will just get a `404 Not Found` error like:

|

||||

|

||||

```JSON

|

||||

{

|

||||

"detail": "Not Found"

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

@@ -1,3 +1,5 @@

|

||||

# Custom Request and APIRoute class

|

||||

|

||||

In some cases, you may want to override the logic used by the `Request` and `APIRoute` classes.

|

||||

|

||||

In particular, this may be a good alternative to logic in a middleware.

|

||||

@@ -13,10 +15,9 @@ For example, if you want to read or manipulate the request body before it is pro

|

||||

|

||||

Some use cases include:

|

||||

|

||||

* Converting non-JSON request bodies to JSON (e.g. [`msgpack`](https://msgpack.org/index.html)).

|

||||

* Converting non-JSON request bodies to JSON (e.g. <a href="https://msgpack.org/index.html" class="external-link" target="_blank">`msgpack`</a>).

|

||||

* Decompressing gzip-compressed request bodies.

|

||||

* Automatically logging all request bodies.

|

||||

* Accessing the request body in an exception handler.

|

||||

|

||||

## Handling custom request body encodings

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -26,14 +27,17 @@ And an `APIRoute` subclass to use that custom request class.

|

||||

|

||||

### Create a custom `GzipRequest` class

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

This is a toy example to demonstrate how it works, if you need Gzip support, you can use the provided [`GzipMiddleware`](./middleware.md#gzipmiddleware){.internal-link target=_blank}.

|

||||

|

||||

First, we create a `GzipRequest` class, which will overwrite the `Request.body()` method to decompress the body in the presence of an appropriate header.

|

||||

|

||||

If there's no `gzip` in the header, it will not try to decompress the body.

|

||||

|

||||

That way, the same route class can handle gzip compressed or uncompressed requests.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### Create a custom `GzipRoute` class

|

||||

@@ -46,8 +50,8 @@ This method returns a function. And that function is what will receive a request

|

||||

|

||||

Here we use it to create a `GzipRequest` from the original request.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note "Technical Details"

|

||||

@@ -59,7 +63,7 @@ Here we use it to create a `GzipRequest` from the original request.

|

||||

|

||||

And those two things, `scope` and `receive`, are what is needed to create a new `Request` instance.

|

||||

|

||||

To learn more about the `Request` check <a href="https://www.starlette.io/requests/" target="_blank">Starlette's docs about Requests</a>.

|

||||

To learn more about the `Request` check <a href="https://www.starlette.io/requests/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette's docs about Requests</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

The only thing the function returned by `GzipRequest.get_route_handler` does differently is convert the `Request` to a `GzipRequest`.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -71,30 +75,35 @@ But because of our changes in `GzipRequest.body`, the request body will be autom

|

||||

|

||||

## Accessing the request body in an exception handler

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

To solve this same problem, it's probably a lot easier to use the `body` in a custom handler for `RequestValidationError` ([Handling Errors](../tutorial/handling-errors.md#use-the-requestvalidationerror-body){.internal-link target=_blank}).

|

||||

|

||||

But this example is still valid and it shows how to interact with the internal components.

|

||||

|

||||

We can also use this same approach to access the request body in an exception handler.

|

||||

|

||||

All we need to do is handle the request inside a `try`/`except` block:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="15 17"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="13 15"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If an exception occurs, the`Request` instance will still be in scope, so we can read and make use of the request body when handling the error:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="18 19 20"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="16 17 18"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Custom `APIRoute` class in a router

|

||||

|

||||

You can also set the `route_class` parameter of an `APIRouter`:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="25"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="26"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this example, the *path operations* under the `router` will use the custom `TimedRoute` class, and will have an extra `X-Response-Time` header in the response with the time it took to generate the response:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="15 16 17 18 19"

|

||||

{!./src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_request_and_route/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

208

docs/en/docs/advanced/custom-response.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,208 @@

|

||||

# Custom Response - HTML, Stream, File, others

|

||||

|

||||

By default, **FastAPI** will return the responses using `JSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

You can override it by returning a `Response` directly as seen in [Return a Response directly](response-directly.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

|

||||

|

||||

But if you return a `Response` directly, the data won't be automatically converted, and the documentation won't be automatically generated (for example, including the specific "media type", in the HTTP header `Content-Type` as part of the generated OpenAPI).

|

||||

|

||||

But you can also declare the `Response` that you want to be used, in the *path operation decorator*.

|

||||

|

||||

The contents that you return from your *path operation function* will be put inside of that `Response`.

|

||||

|

||||

And if that `Response` has a JSON media type (`application/json`), like is the case with the `JSONResponse` and `UJSONResponse`, the data you return will be automatically converted (and filtered) with any Pydantic `response_model` that you declared in the *path operation decorator*.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note

|

||||

If you use a response class with no media type, FastAPI will expect your response to have no content, so it will not document the response format in its generated OpenAPI docs.

|

||||

|

||||

## Use `ORJSONResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

For example, if you are squeezing performance, you can install and use <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`orjson`</a> and set the response to be `ORJSONResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

Import the `Response` class (sub-class) you want to use and declare it in the *path operation decorator*.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 7"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial001b.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! info

|

||||

The parameter `response_class` will also be used to define the "media type" of the response.

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, the HTTP header `Content-Type` will be set to `application/json`.

|

||||

|

||||

And it will be documented as such in OpenAPI.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

The `ORJSONResponse` is currently only available in FastAPI, not in Starlette.

|

||||

|

||||

## HTML Response

|

||||

|

||||

To return a response with HTML directly from **FastAPI**, use `HTMLResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

* Import `HTMLResponse`.

|

||||

* Pass `HTMLResponse` as the parameter `content_type` of your *path operation*.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 7"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! info

|

||||

The parameter `response_class` will also be used to define the "media type" of the response.

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, the HTTP header `Content-Type` will be set to `text/html`.

|

||||

|

||||

And it will be documented as such in OpenAPI.

|

||||

|

||||

### Return a `Response`

|

||||

|

||||

As seen in [Return a Response directly](response-directly.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, you can also override the response directly in your *path operation*, by returning it.

|

||||

|

||||

The same example from above, returning an `HTMLResponse`, could look like:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 7 19"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial003.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! warning

|

||||

A `Response` returned directly by your *path operation function* won't be documented in OpenAPI (for example, the `Content-Type` won't be documented) and won't be visible in the automatic interactive docs.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! info

|

||||

Of course, the actual `Content-Type` header, status code, etc, will come from the `Response` object your returned.

|

||||

|

||||

### Document in OpenAPI and override `Response`

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to override the response from inside of the function but at the same time document the "media type" in OpenAPI, you can use the `response_class` parameter AND return a `Response` object.

|

||||

|

||||

The `response_class` will then be used only to document the OpenAPI *path operation*, but your `Response` will be used as is.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Return an `HTMLResponse` directly

|

||||

|

||||

For example, it could be something like:

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="7 23 21"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial004.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this example, the function `generate_html_response()` already generates and returns a `Response` instead of returning the HTML in a `str`.

|

||||

|

||||

By returning the result of calling `generate_html_response()`, you are already returning a `Response` that will override the default **FastAPI** behavior.

|

||||

|

||||

But as you passed the `HTMLResponse` in the `response_class` too, **FastAPI** will know how to document it in OpenAPI and the interactive docs as HTML with `text/html`:

|

||||

|

||||

<img src="/img/tutorial/custom-response/image01.png">

|

||||

|

||||

## Available responses

|

||||

|

||||

Here are some of the available responses.

|

||||

|

||||

Have in mind that you can use `Response` to return anything else, or even create a custom sub-class.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! note "Technical Details"

|

||||

You could also use `from starlette.responses import HTMLResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

**FastAPI** provides the same `starlette.responses` as `fastapi.responses` just as a convenience for you, the developer. But most of the available responses come directly from Starlette.

|

||||

|

||||

### `Response`

|

||||

|

||||

The main `Response` class, all the other responses inherit from it.

|

||||

|

||||

You can return it directly.

|

||||

|

||||

It accepts the following parameters:

|

||||

|

||||

* `content` - A `str` or `bytes`.

|

||||

* `status_code` - An `int` HTTP status code.

|

||||

* `headers` - A `dict` of strings.

|

||||

* `media_type` - A `str` giving the media type. E.g. `"text/html"`.

|

||||

|

||||

FastAPI (actually Starlette) will automatically include a Content-Length header. It will also include a Content-Type header, based on the media_type and appending a charset for text types.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="1 18"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/response_directly/tutorial002.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### `HTMLResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Takes some text or bytes and returns an HTML response, as you read above.

|

||||

|

||||

### `PlainTextResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Takes some text or bytes and returns an plain text response.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 7 9"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial005.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### `JSONResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Takes some data and returns an `application/json` encoded response.

|

||||

|

||||

This is the default response used in **FastAPI**, as you read above.

|

||||

|

||||

### `ORJSONResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

A fast alternative JSON response using <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`orjson`</a>, as you read above.

|

||||

|

||||

### `UJSONResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

An alternative JSON response using <a href="https://github.com/ultrajson/ultrajson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`ujson`</a>.

|

||||

|

||||

!!! warning

|

||||

`ujson` is less careful than Python's built-in implementation in how it handles some edge-cases.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 7"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial001.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

It's possible that `ORJSONResponse` might be a faster alternative.

|

||||

|

||||

### `RedirectResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Returns an HTTP redirect. Uses a 307 status code (Temporary Redirect) by default.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 9"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial006.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### `StreamingResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Takes an async generator or a normal generator/iterator and streams the response body.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 14"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial007.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

#### Using `StreamingResponse` with file-like objects

|

||||

|

||||

If you have a file-like object (e.g. the object returned by `open()`), you can return it in a `StreamingResponse`.

|

||||

|

||||

This includes many libraries to interact with cloud storage, video processing, and others.

|

||||

|

||||

```Python hl_lines="2 10 11"

|

||||

{!../../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial008.py!}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

!!! tip

|

||||

Notice that here as we are using standard `open()` that doesn't support `async` and `await`, we declare the path operation with normal `def`.

|

||||

|

||||

### `FileResponse`

|

||||

|

||||

Asynchronously streams a file as the response.

|

||||

|

||||

Takes a different set of arguments to instantiate than the other response types:

|

||||

|

||||

* `path` - The filepath to the file to stream.

|

||||

* `headers` - Any custom headers to include, as a dictionary.

|

||||

* `media_type` - A string giving the media type. If unset, the filename or path will be used to infer a media type.

|

||||